The quadratic $O(N^2)$ complexity of self-attention has long been a major computational bottleneck in modern large models. This year, one of the most active directions for improving attention mechanisms has been sparse attention: instead of attending to all key–value (KV) tokens, each query attends only to a small subset of important tokens. Representative works in this direction include MoBA from Kimi and NSA from DeepSeek.

However, despite their sparsity, these methods do not fundamentally reduce the asymptotic complexity of attention. Their overall runtime still grows with sequence length $N$ following an $O(N^2)$ trend.

To address this limitation, our recent work, Log-linear Sparse Attention (LLSA), reduces the complexity of sparse attention to $O(N \log N)$ at the algorithmic level. In addition, we provide a highly optimized Triton implementation of LLSA tailored to modern GPU architectures, and employ efficient sparse algorithms to minimize the overhead introduced by sparsity itself. We validate the effectiveness of LLSA on pure pixel-space DiT generation tasks without VAE and without patchification. On pixel sequences as long as $512 \times 512$, LLSA achieves generation quality comparable to full attention, while significantly reducing computation time.

In this blog post, I introduce our arXiv paper Trainable Log-linear Sparse Attention for Efficient Diffusion Transformers, and conclude with my own assessment of the work and possible future directions. Our high-performance Triton implementation of LLSA has also been open-sourced. We warmly welcome fellow researchers to use our method, and to discuss or collaborate with us after reading the paper.

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.16615

GitHub: https://github.com/SingleZombie/LLSA

Background

First, let us clarify the scope of LLSA. As stated in the paper title, LLSA is a trainable attention mechanism. Therefore, it differs fundamentally from inference-time acceleration methods for pretrained models such as Sparse VideoGen. LLSA does not aim to approximate full attention outputs as closely as possible; instead, it only needs to enable successful training of Transformers equipped with this attention mechanism. In this sense, LLSA is more directly comparable to mechanisms such as MoBA (Mixture of Block Attention) and NSA (Native Sparse Attention), and enjoys a much larger design space.

In this section, I first provide background to clarify the problem we aim to solve, and then briefly review related prior work.

Sparsifying Attention

The attention operation can be written as

Here, $\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}$, where $N$ is the sequence length and $d$ is the feature dimension. We refer to these as queries, keys, and values.

This formulation aggregates $N$ queries into matrix form. If we consider a single query $q \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times d}$, the operation is easier to interpret: we compute normalized similarities $p = \text{softmax}(q\mathbf{K}^{\intercal})$, then obtain the attention output $o = p\mathbf{V}$. Concatenating all $o$ yields the final output $\mathbf{O}$.

From a complexity perspective, standard full attention is slow because each of the $N$ queries attends to all $N$ keys and values, resulting in $O(N^2)$ complexity. Equivalently, the matrix multiplication $\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^{\intercal}$ has complexity $O(N^2 d)$, which reduces to $O(N^2)$ when $d$ is treated as a constant. As sequence length increases, attention quickly dominates runtime compared to linear-time components such as MLPs or normalization layers.

Many studies have observed that attention matrices $\mathbf{P}$ in pretrained models are sparse: for each query, most key similarities are close to zero and can be ignored. This naturally leads to the idea of Top-$K$ attention—selecting only the $K$ most important keys and values per query.

While this idea is correct in principle, it does not automatically lead to acceleration. To find the Top-$K$, one must first compute all $O(N^2)$ query–key similarities. If those similarities are already computed, applying sparsity afterward provides little benefit. Thus, Top-$K$ sparse attention can only be efficient if query–key similarities can themselves be computed efficiently.

Modern Top-$K$ sparse attention methods therefore rely on approximate similarity estimation. To understand them, we first review Block Sparse FlashAttention.

Block Sparse FlashAttention

Modern GPU programming is fundamentally based on parallelism: a GPU can process $B$ identical operations simultaneously. For example, when summing two vectors of length $N$, we do not write a loop of length $N$ that processes one element at a time; instead, we process $B$ elements per iteration using a loop of length $N/B$.

FlashAttention adopts this principle by performing attention computation in blocks. Suppose $\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}$ are partitioned into $N/B$ blocks, where block $i$ contains $\mathbf{Q}_i, \mathbf{K}_i, \mathbf{V}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times d}$. We can then launch $N/B$ programs, each computing outputs $\mathbf{O}_i$ for one query block. Inside each program, a loop of length $N/B$ iterates over key–value blocks.

This structure naturally supports block sparsity. If a sparse algorithm determines that $\mathbf{Q}_i$ does not need to attend to $\mathbf{K}_j$, the $j$-th iteration of the $i$-th program can be skipped. The choice of sparsity pattern is unrestricted—for example, sliding-window attention.

Top-$K$ Block Sparse Attention

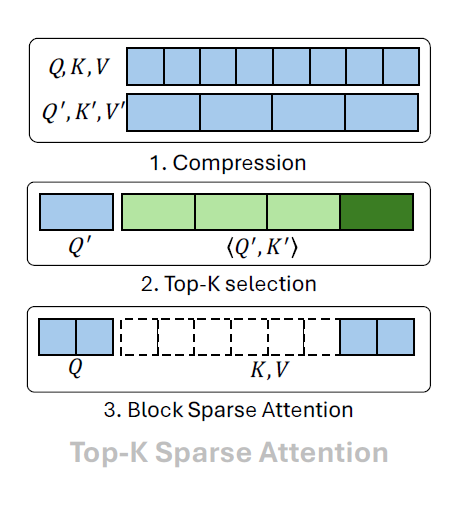

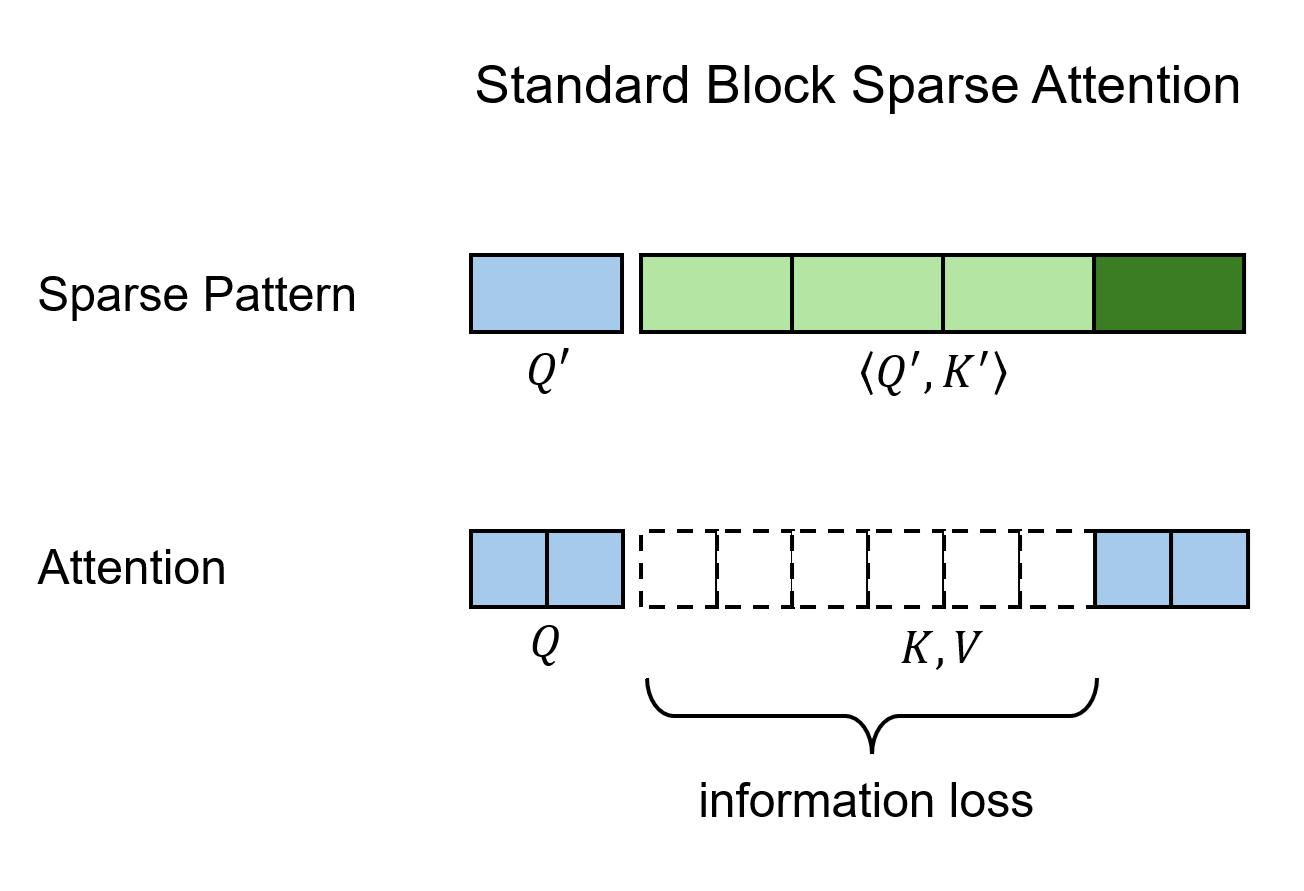

With Block Sparse FlashAttention in mind, an efficient Top-$K$ sparse attention algorithm emerges naturally. The key idea is to construct coarse representations that summarize each block, compute Top-$K$ sparsity on these coarse features, and then apply block-sparse attention. The steps are:

- Apply $B$-stride average pooling to $\mathbf{Q}$ and $\mathbf{K}$, producing $\mathbf{Q}’, \mathbf{K}’ \in \mathbb{R}^{T \times d}$ with $T = N/B$.

- Compute inner products between $\mathbf{Q}’$ and $\mathbf{K}’$, and select the Top-$K$ key blocks for each query block.

- Execute Block Sparse FlashAttention using the resulting sparse block indices.

This description abstracts the core idea behind many modern Top-$K$ sparse attention methods, including MoBA, NSA, and later VMoBA, VSA, and SLA.

Let us analyze the complexity. The runtime is dominated by Top-$K$ search (step 2) and sparse attention computation (step 3).

- Top-$K$ search involves $O((N/B)^2)$ inner products.

- Sparse attention costs $O(NKB)$, since each query attends to $KB$ keys.

When $N$ is small, sparse attention dominates. As $N$ grows, the $O(N^2)$ term inevitably dominates. Thus, such methods do not fundamentally improve attention complexity; they only yield a constant-factor speedup (at most $B^2$). In contrast, the goal of Log-linear Sparse Attention (LLSA) is to eliminate the $O(N^2)$ term entirely.

Related Work

In NLP, popular trainable sparse attention mechanisms include MoBA and NSA. Concurrently, SpargeAttention was proposed as a pooling-and-filtering-based sparse attention applicable to both NLP and CV. In CV, VMoBA adapts MoBA to vision tasks, while VSA (Video Sparse Attention) and SLA (Sparse-Linear Attention) ressolve the information loss caused by sparsity in VMoBA. VSA computes a coarse attention output and adds it to sparse attention, while SLA uses linear attention to approximate contributions from non-Top-$K$ keys.

Hierarchical decompositions with $O(\log N)$ levels are a recurring idea in attention optimization. Early examples include H-Transformer and Fast Multipole Attention. More recently, Radial Attention achieves $O(N\log N)$ complexity via a static sparsity pattern for video. Log-linear Attention improves linear attention quality by maintaining $O(\log N)$ states per query using Fenwick Tree. The method most similar to ours is Multi-Resolution Attention (MRA), which lacks an efficient FlashAttention-compatible GPU implementation and was not validated on ultra-long sequence generation.

LLSA targets Pixel DiT. At the time of this work, Pixel DiT research was limited to PixelFlow and PixNerd. More recently, JiT, DiP, DeCo, and PixelDiT appeared on arXiv, but all rely on patchification to reduce token counts. No prior work trained DiT without VAE and without patchification, due to the prohibitive attention cost. Our work directly addresses this challenge and validates LLSA on high-resolution pure pixel DiT generation.

Log-linear Sparse Attention: Method

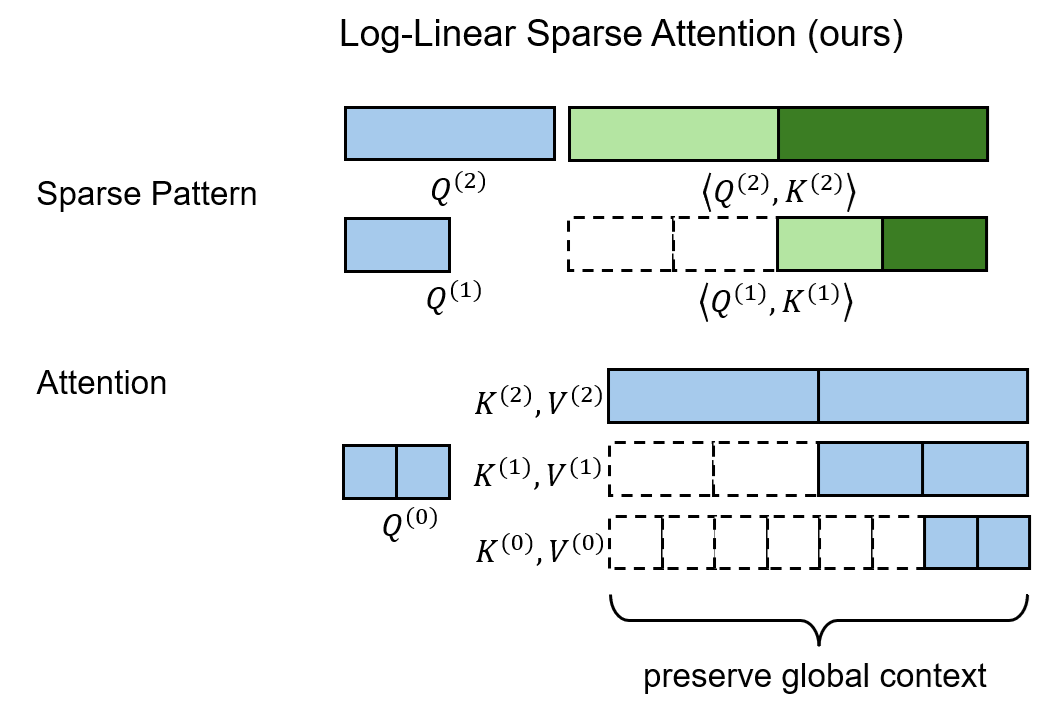

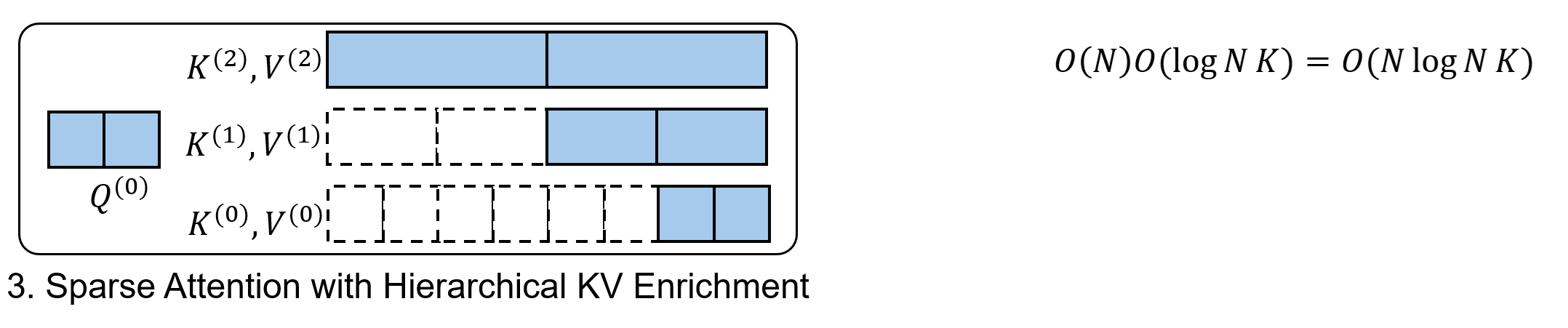

The figure below provides an overview of the method.

In short, LLSA upgrades the conventional two-level sparsity structure into a multi-level hierarchy. Moreover, in the final sparse attention computation, LLSA not only uses the finest-grained keys/values, but also incorporates coarser keys/values from multiple hierarchy levels. Details are as follows.

Attention Algorithm

Hierarchical Compression

We partition the token sequence into $

L = \log_B N - 1

$ levels. Concretely, we repeatedly apply $B$-stride average pooling to compress the original token features

into $L$ sets of coarser tokens. At level $l$, we have

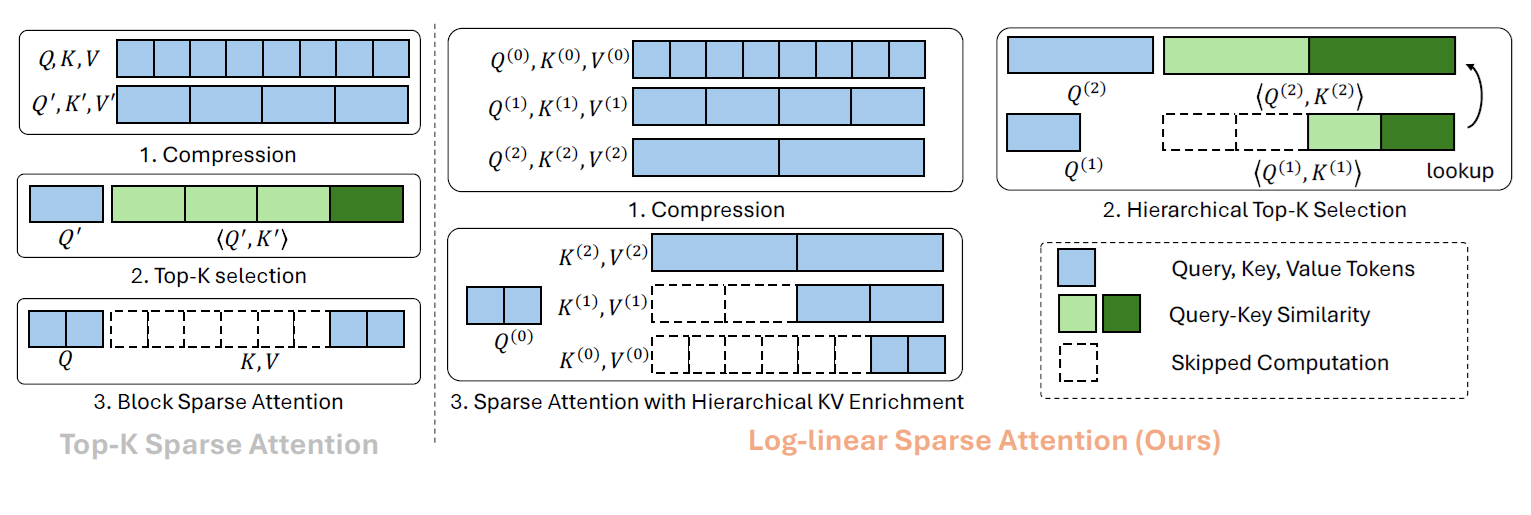

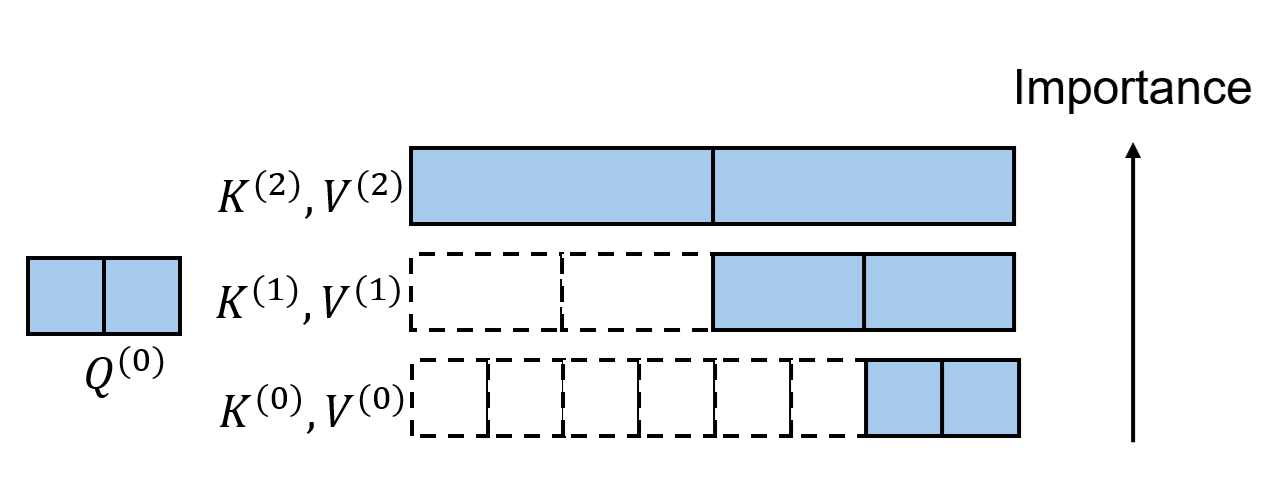

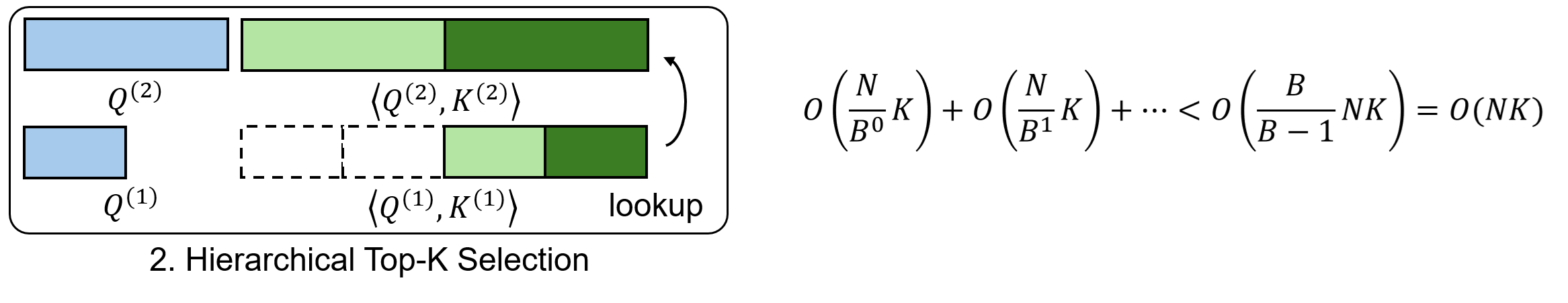

Hierarchical Top-$K$ Selection

We perform Top-$K$ selection in a top-down manner, refining from coarse to fine, to identify the Top-$K$ most similar key blocks for each query block.

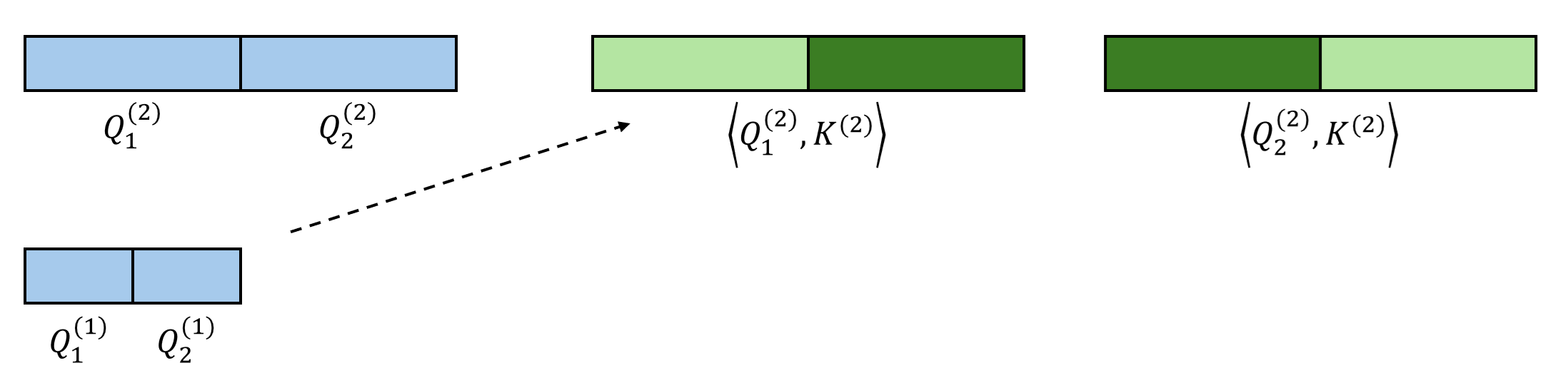

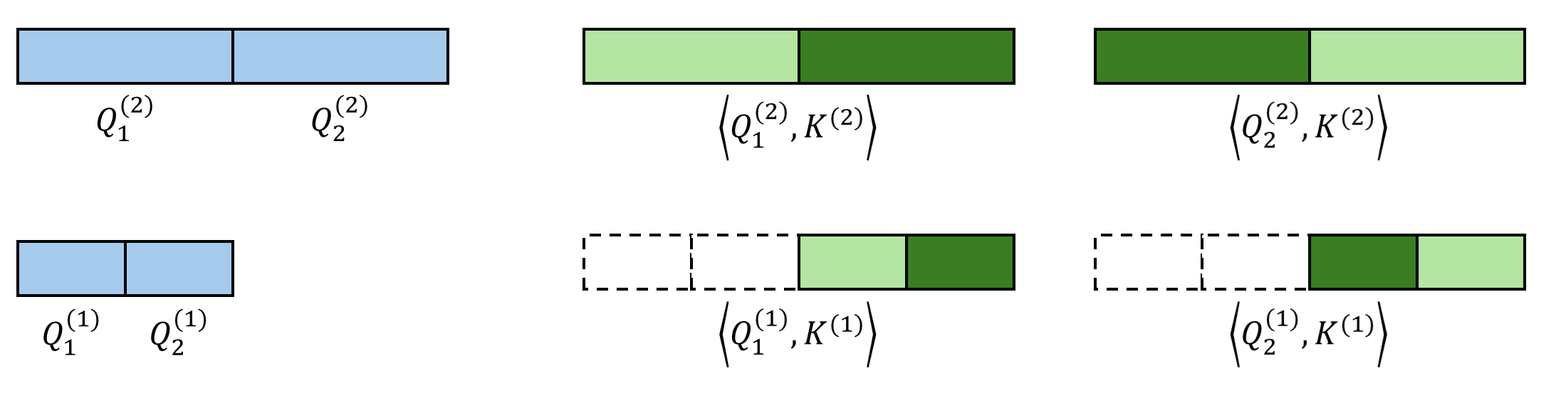

Consider the example $N=8, B=2, K=1$. We start by computing full similarities at the top level (level $L$) between coarse queries and keys.

Starting from the second-coarsest level, we recursively leverage the sparse indices from the previous level to further select Top-$K$ candidates. Here, we assume that all fine queries within the same coarse block share the same sparse pattern at this level. For example, in the figure below, both $\mathbf{Q}^{(1)}_1$ and $\mathbf{Q}^{(1)}_2$ belong to the coarser block $\mathbf{Q}^{(2)}_1$, and thus they should only attend to the key tokens corresponding to $\mathbf{K}^{(2)}_2$.

At the previous level, each query has $K$ candidate coarse key blocks. At the current (finer) level, since the granularity increases, each query has $KB$ candidate key blocks. Among these $KB$ candidates, we run Top-$K$ selection again. This recursion continues until the bottom level.

In the end, we obtain the indices of Top-$K$ key blocks for each query block at all levels.

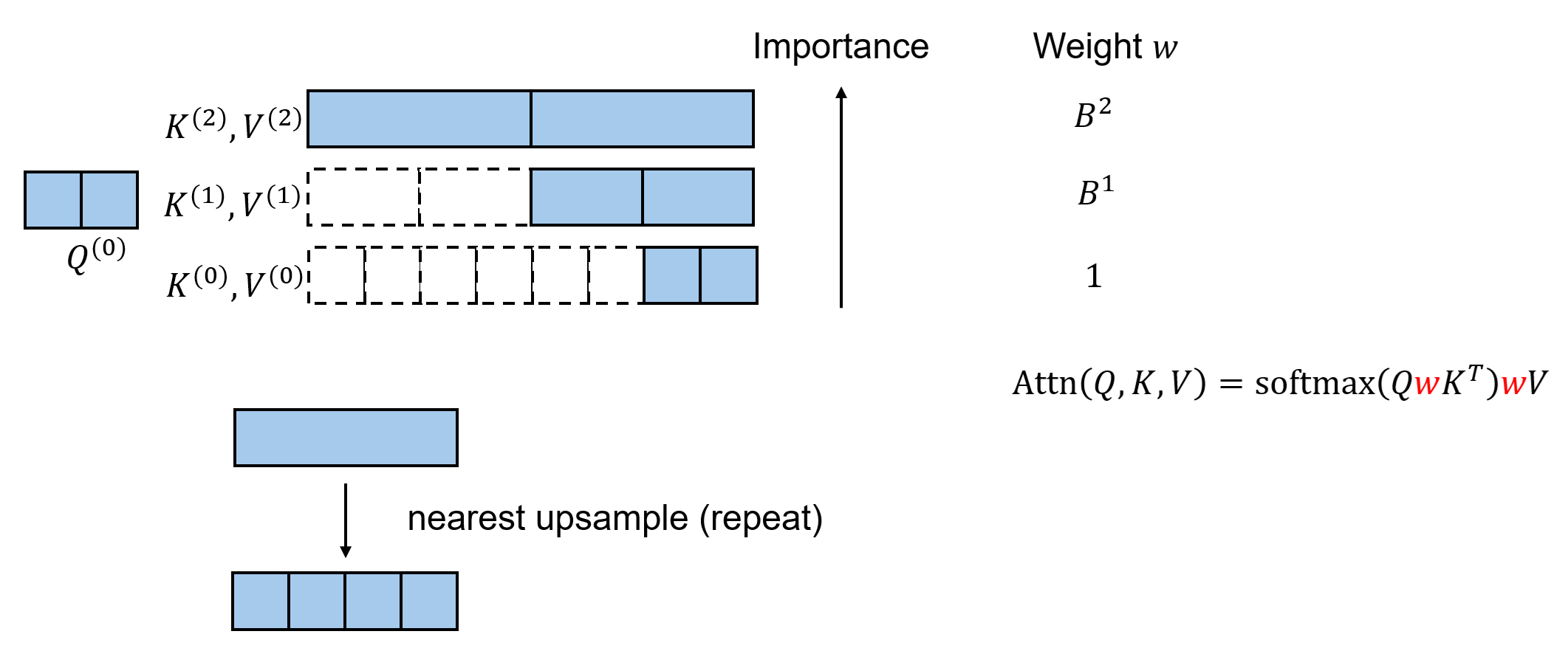

Hierarchical KV Enrichment

In standard sparse attention, attending only to a sparse subset of K/V tokens inevitably causes information loss.

LLSA mitigates this issue by exploiting the multi-level sparse patterns discovered during hierarchical Top-$K$ selection. Instead of attending only to the finest K/V tokens, LLSA also includes coarser K/V tokens from multiple levels in the final sparse attention computation. This allows each query to preserve global context.

KV Reweighting

The above is not yet optimal. Intuitively, coarser tokens summarize more information and should have higher importance. However, a naive implementation assigns the same weight to K/V tokens from all levels.

We therefore assume that the information in a coarse K/V token can be approximately reconstructed into its fine tokens via nearest-neighbor upsampling (i.e., repeat). Under this assumption, we do not need to explicitly upsample; instead, we can assign different weights to tokens from different levels during attention. Specifically, a level-$l$ token is assigned weight $B^l$, and this weight is applied multiplicatively to both K and V.

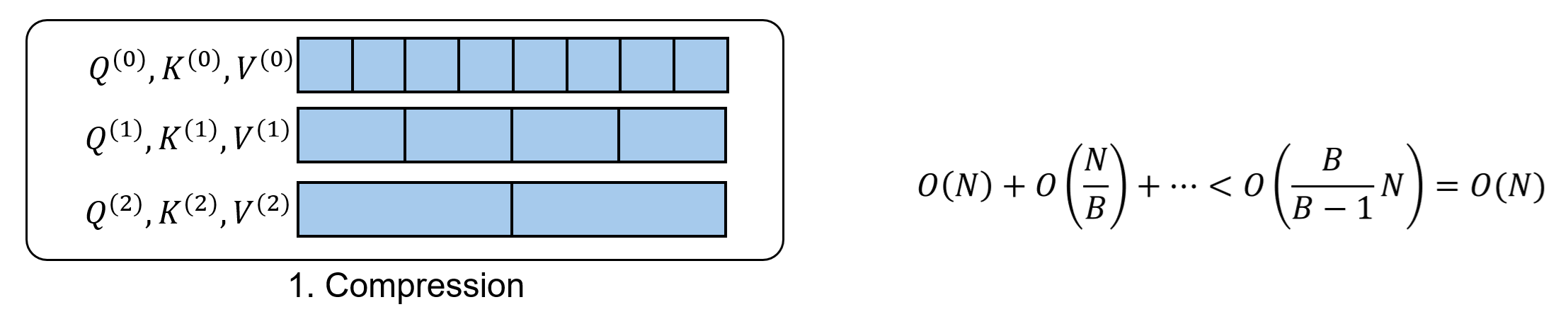

Complexity Analysis

Does LLSA truly accelerate prior sparse attention methods? Let us analyze its complexity (assuming $B$ is a constant).

Hierarchical compression. We can count the total number of tokens across levels. Token counts form a geometric series, whose sum is bounded by a constant (dependent on $B$) times $N$. Hence, the complexity is $O(N)$.

Hierarchical Top-$K$ selection. Similarly, the total number of queries across levels is $O(N)$. At each level, the number of candidate key tokens evaluated per query is $KB$, yielding total complexity $O(NK)$.

For simplicity, we do not analyze the complexity of the Top-$K$ algorithm itself. Its complexity depends on the specific implementation, and runtime is tightly coupled with sequence length and the parallel algorithm used. In terms of asymptotic scaling with $N$, when $K$ and $B$ are constants, Top-$K$ selection is also $O(N)$.

Final attention computation. There are $O(N)$ queries and $O(K\log N)$ key/value blocks per query. Therefore, this step costs $O(NK\log N)$.

If we treat $K$ as a constant as well (which is typical in practice), the overall complexity of LLSA is $O(N\log N)$. In other words, we have reduced the $O(N^2)$ complexity of prior sparse attention mechanisms.

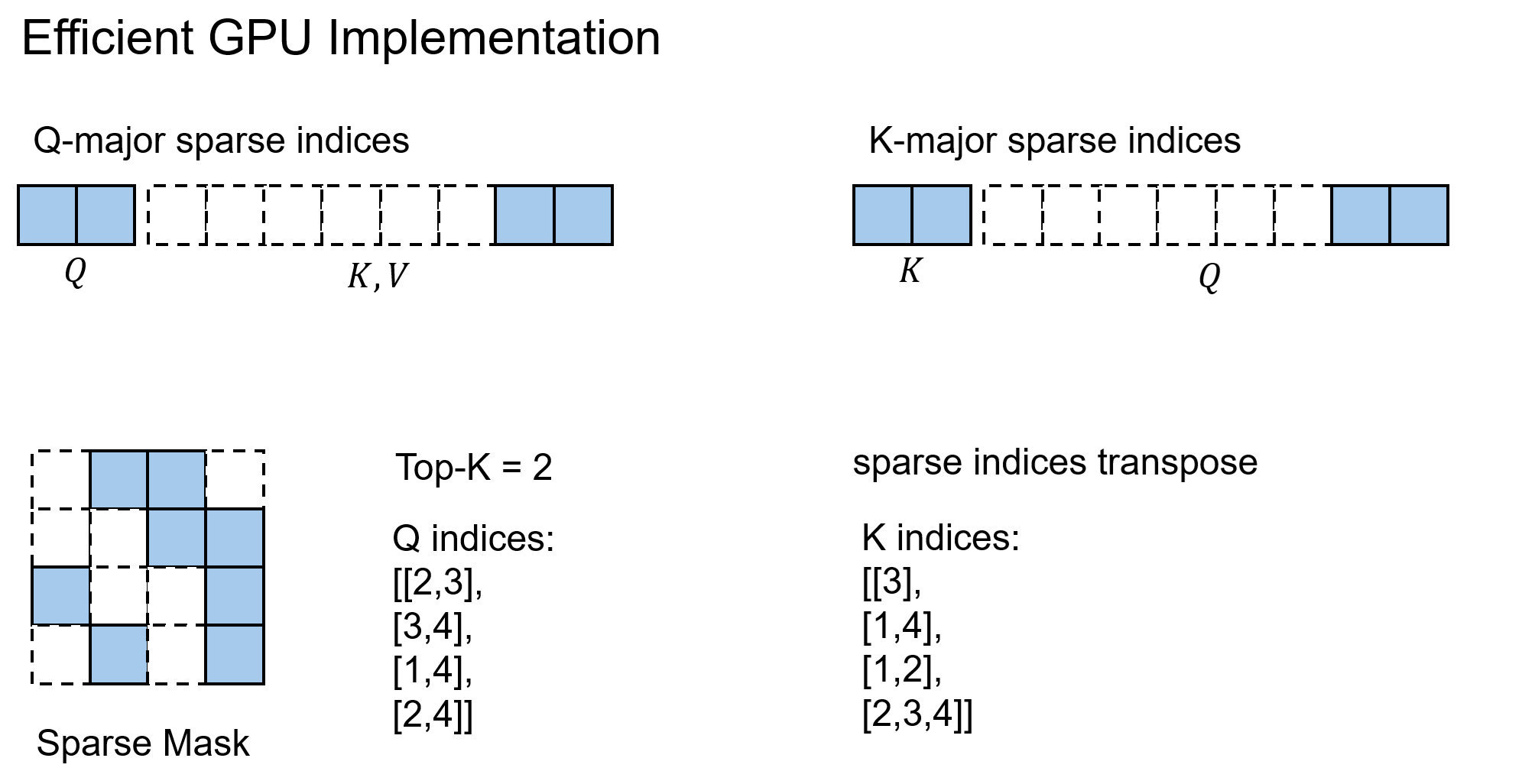

High-Performance GPU Implementation

In modern deep learning frameworks, a new operator must be adapted to GPU parallel programming. LLSA is designed to be compatible with FlashAttention.

Concretely, for all parts involving sparse access (sparse Top-$K$, sparse attention), we can replace dense iteration over all K/V tokens with iteration over sparse indices. We then gather the corresponding K/V values by index. Dense loops that were originally $O(N)$ are reduced to $O(K)$.

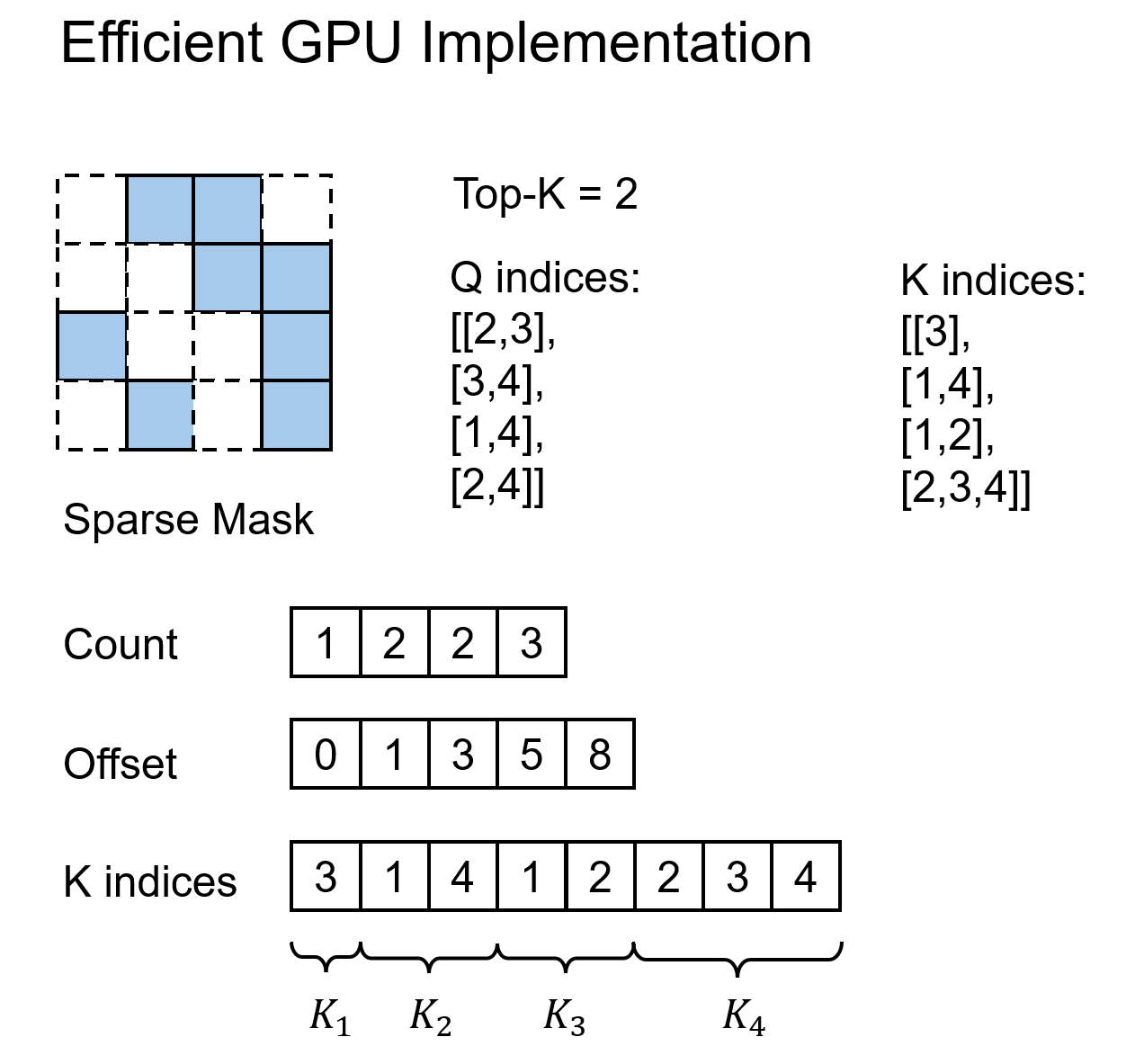

However, there is one key challenge in implementation: Top-$K$ selection naturally yields Q-major sparse indices (i.e., which K each Q attends to), but does not directly provide K-major sparse indices (i.e., which Q attends to a given K). Efficient gradient computation for K/V requires K-major indices. Therefore, we must implement a sparse index transpose algorithm that converts Q-major indices into K-major indices.

Fortunately, this problem is well studied in sparse matrix multiplication. We directly adopt mature algorithms from that literature. The basic idea is as follows: since the length of K-major indices is variable, we store all K-to-Q indices in a flattened 1D array. This corresponds to flattening a ragged 2D K-major structure. To locate the segment belonging to each K, we maintain an auxiliary offset array that stores the start and end offsets for each K.

Without this optimized approach, one would have to represent sparsity using a dense mask matrix indicating whether each (Q, K) pair is valid. This would degrade complexity back to $O(N^2)$. Many prior methods rely on this less efficient strategy.

Experiments

Pixel DiT Setup

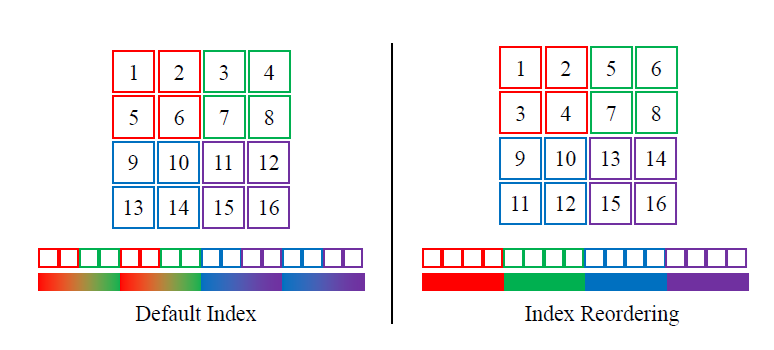

To verify that LLSA indeed reduces the complexity of attention, we train a pure pixel-space DiT without VAE and without patchification on long pixel token sequences. To adapt LLSA to 2D data, we employ index reordering. To accelerate training, we use noise rescaling and low-resolution pretraining.

Index reordering. LLSA is designed for 1D sequences. Since it repeatedly applies average downsampling over adjacent groups of $B$ tokens, it is beneficial if adjacent tokens are semantically correlated. For 2D images, the most natural approach is to map 2D patches into a 1D ordering that preserves locality as much as possible. Following prior work, we adopt the index reordering scheme below.

Noise rescaling. Prior works such as Simple Diffusion and SD3 suggest that higher-resolution data should receive stronger noise. In our experiments, the most effective approach is to multiply the noise term by a factor $s ,(s\ge 1)$. For example, under rectified flow, the noising formula becomes

Empirically, for images of sequence length $n\times n,(n>64)$, we set $

s = \frac{n}{64},

$ i.e., we align the signal-to-noise ratio to that of $64\times 64$ images.

Pretraining. Following multi-stage training strategies used in large-scale text-to-image models such as SD3, we first pretrain on low-resolution images and then progressively finetune at higher resolutions.

DiT architecture. We replace standard DiT positional encoding with RoPE, and add qk-norm to stabilize bfloat16 training.

We do not upgrade the backbone to LightningDiT or DDT, nor do we use REPA.

Metrics. Unless otherwise stated, our default evaluation protocol is: FID is computed on 10,000 samples generated with 20 denoising steps. Throughput is measured in 1,000 pixel tokens per second. All throughput numbers are reported on a single H200 GPU.

Ablations

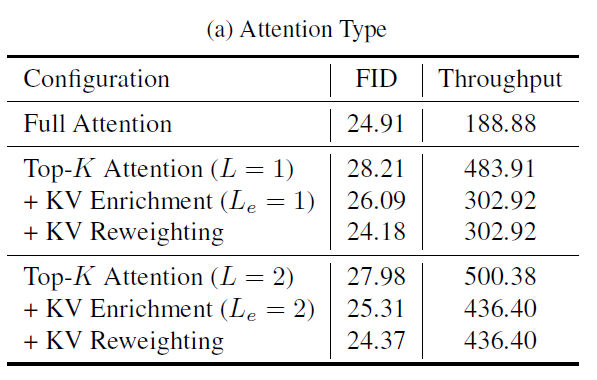

Unless otherwise specified, ablations are evaluated on models trained for 20 epochs on FFHQ-128. The default hyperparameters are $B=16$ and $K=8$. Key ablation results are shown below.

In the table, $L$ denotes the number of hierarchy levels, and $L_e$ denotes how many levels use KV Enrichment. The main takeaways are:

Comparing $L=1$ vs. $L=2$, moving to $L=2$ significantly improves speed while slightly degrading FID (primarily because the number of KV tokens accessed is greatly reduced). This supports that the $\log N$-level hierarchical design indeed improves computational efficiency.

Both KV Enrichment and KV Reweighting are effective. In fact, the resulting sparse attention can even outperform full attention in terms of FID.

We also train an $L=3$ LLSA model on FFHQ at $512\times 512$. The outcome matches expectations: as sequence length increases, increasing $L$ yields runtime that grows roughly as $O(N\log N)$. However, since fewer KV tokens are used, speed improves at the cost of slightly worse quality.

The paper and appendix contain more ablation results. Overall, every design choice—both in attention and in training—contributes positively.

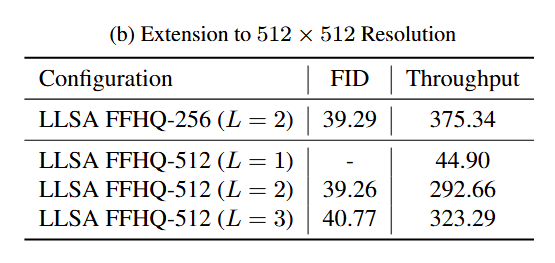

Comparisons

We compare LLSA against VSA and SLA, and briefly discuss VMoBA. To my knowledge, these are the three recent works on trainable sparse attention for DiT. If we focus only on which key blocks are used (ignoring image/video handling details), the methods can be summarized as:

- VMoBA: VMoBA (and MoBA) are equivalent to the Top-$K$ attention described earlier.

- VSA: Compute a coarse attention output on pooled Q/K/V, then add it to the sparse attention output.

- SLA: Use an additional linear attention to approximate contributions from keys outside Top-$K$, then add it to the sparse attention output.

To ensure fairness, we re-implement VSA and SLA inside our training environment and match hyperparameters as closely as possible. Since their GPU backward implementations are relatively inefficient, for a fair speed comparison, we upgrade the backward pass of VSA and SLA to a sparse-index-convolution style implementation.

Moreover, because we enable KV Enrichment, for the same $K$, LLSA accesses more K/V tokens during sparse attention. For fairness in quality comparison, we increase $K$ for VSA and SLA so that the number of K/V tokens they actually access matches LLSA’s effective K/V count.

Results on FFHQ are as follows: LLSA is both faster and better.

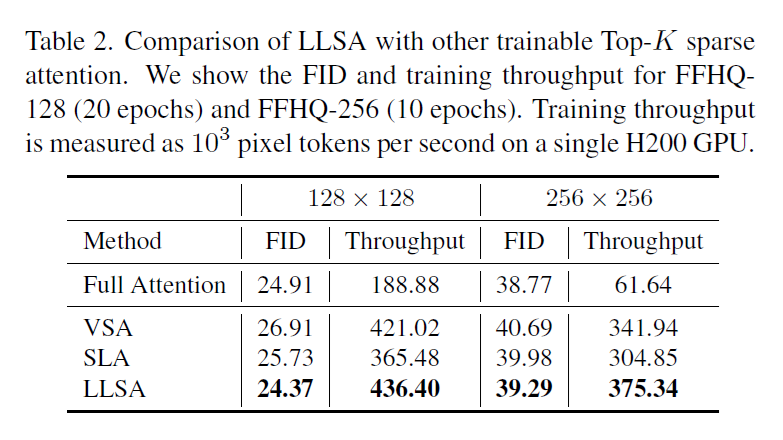

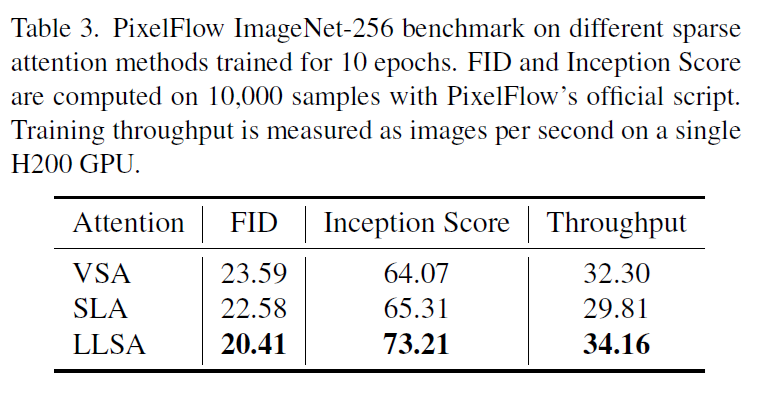

We also run a validation experiment on ImageNet-256. To finish training within limited time, we adopt PixelFlow with patch size = 4 as the DiT backbone, and replace its full attention with VSA, SLA, or LLSA. Results after 10 epochs are shown below.

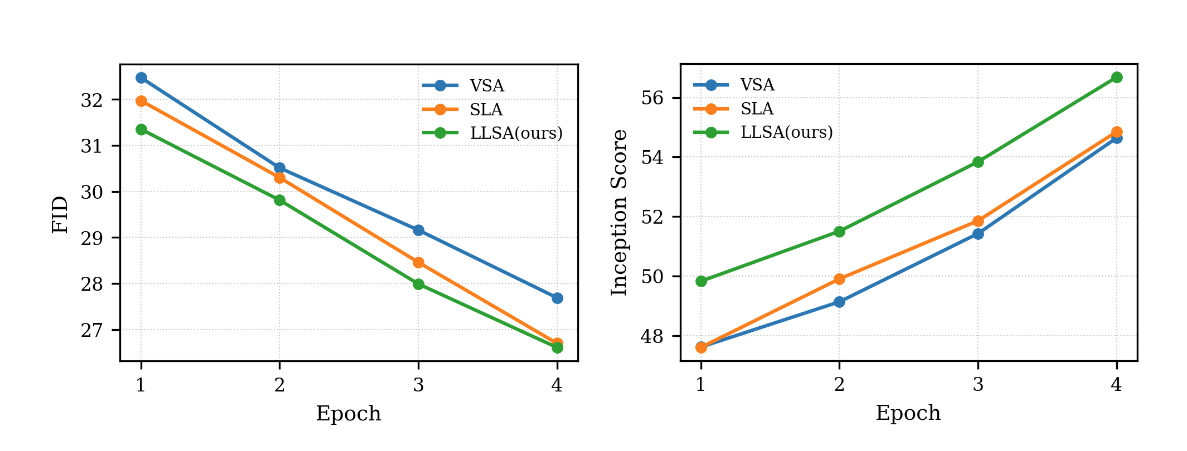

Metrics during the first four epochs are shown below.

We can see that—even under a conservative experimental setup—LLSA is consistently faster and better than prior sparse attention methods on both FFHQ and ImageNet. This outcome is unsurprising. When designing the attention mechanism, I experimented with many ways of incorporating coarse K/V information. Ultimately, I found that introducing multiple computation branches and summing their outputs (as in VSA/SLA) is consistently inferior to performing a single attention operation that jointly attends to pooled K/V and fine K/V. Thus, even ignoring the $O(\log N)$ acceleration itself, the “coarse+fine K/V in one attention” design improves generation quality compared to prior approaches.

Efficiency

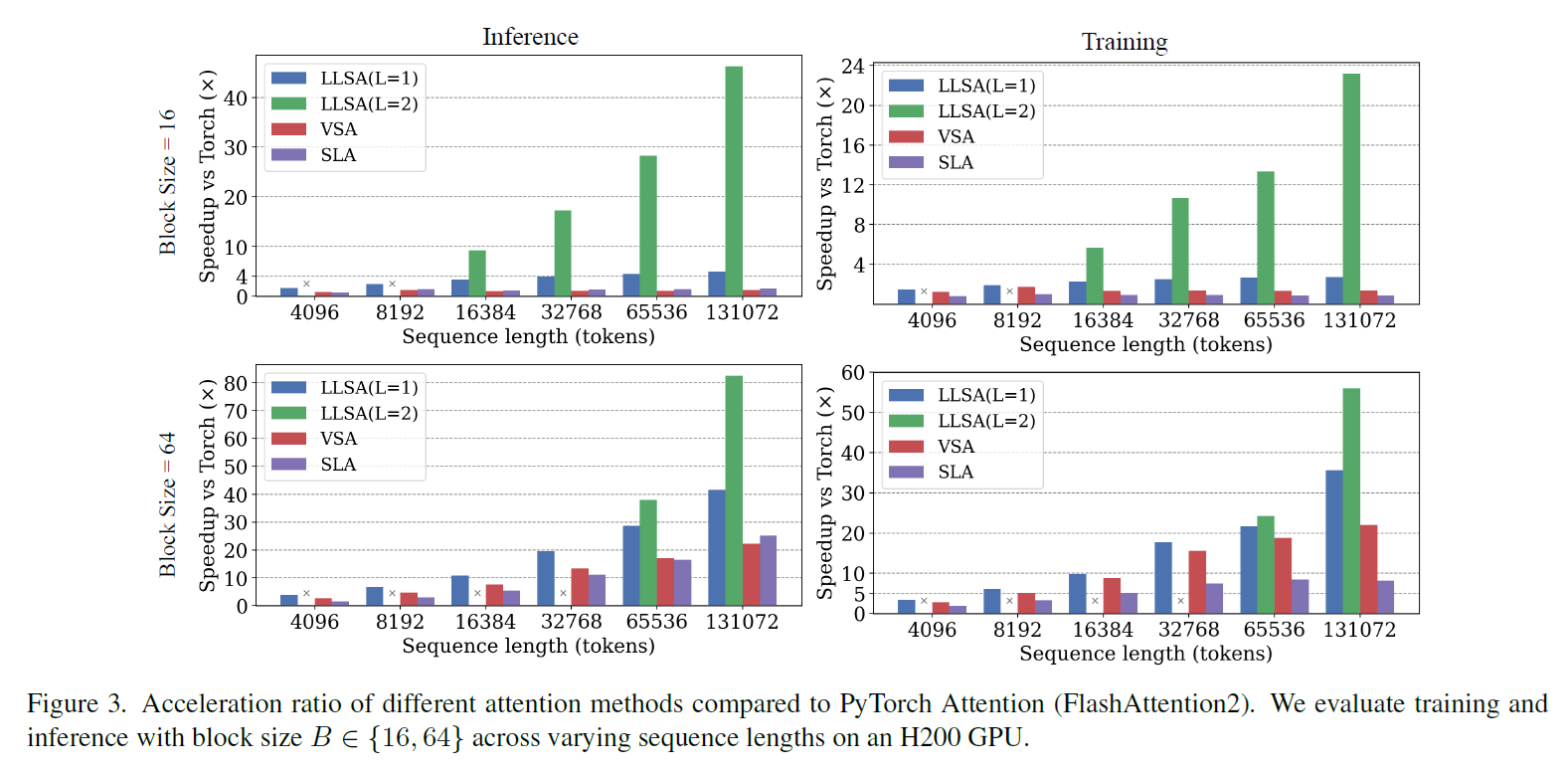

We separately compare inference and training costs (reported as speedup over full attention) across different $B$ values and sequence lengths. Here we use the unoptimized VSA/SLA code. LLSA exhibits a clear efficiency advantage.

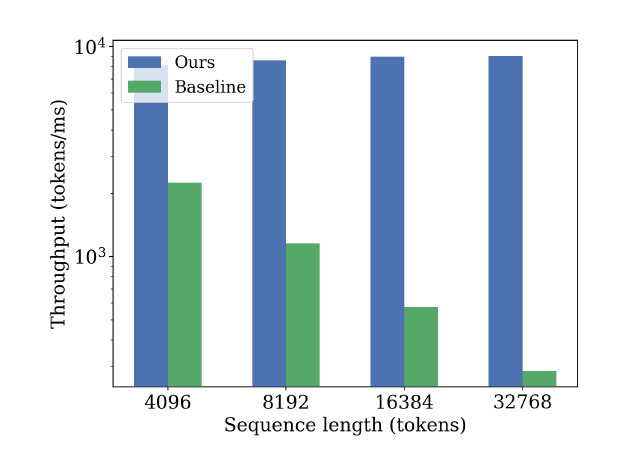

We also validate the effectiveness of sparse-index-transpose-based backward. We compare the backward speed of LLSA against a baseline backward that uses a dense sparse mask. Since our algorithm is $O(N)$, throughput remains nearly constant across different sequence lengths.

These experiments demonstrate that LLSA also improves upon prior methods in terms of GPU implementation efficiency.

Personal Assessment of the Paper

Based on the experimental results, LLSA consistently outperforms prior methods in terms of efficiency, quality, and GPU implementation. Rather than repeating these results, I will focus on what I consider to be the more interesting limitations of the work.

That said, the paper has two notable weaknesses.

First weakness: One clear limitation of this work is that we do not report fully converged ImageNet-256 results.This is primarily due to the extreme training cost required when attention is applied over full-resolution pixel tokens.

Then why we choose pixel DiT as validation task? Prior methods such as VSA/SLA validate on pretrained video DiTs, where token counts are indeed large and suitable. However, their experimental datasets and evaluation protocols are not very standardized. Furthermore, the VSA paper explicitly states it used 128 GPUs, far beyond what I have access to. Thus, for both fairness and resource reasons, I did not want to choose video generation as the validation task.

High-resolution pure pixel DiT generation is arguably the most fair and clean task for our purpose. Yet even in this setting, the token count is so large that we cannot train as long as DiTs on compressed ImageNet-256 setups. Typically, such DiTs have an effective compression ratio of $16\times 16$. Even under the most optimistic linear scaling assumption, we would need $256\times$ more compute to match their number of training steps. Once we choose “optimize attention complexity” as the goal, it becomes almost inevitable that we cannot afford fully converged training. We therefore settle for comparing methods under limited training budgets.

Second weakness: the paper does not analyze why the hierarchical design is effective. It lacks “theoretical analysis” or strong motivation, and focuses more on implementation details.

This issue is not as severe. Many attention optimization papers primarily present implementation designs. Missing theoretical explanations might lower review scores, but does not invalidate the method. Effectiveness is mainly supported by experiments. If reviewers question this point, we can only acknowledge the limitation.

Finally, there is another point that only attention experts might notice. The method design is extremely similar to Multi-Resolution Attention (MRA), with the key difference that MRA does not provide a high-performance implementation. Does this imply insufficient novelty?

Frankly speaking, when the project started, my goal was to improve upon NSA/VSA-style methods, and I was unaware that an early hierarchical $O(\log N)$ paper already existed. I never believed such an optimization is “unthinkable”—hierarchical algorithmic ideas are common in computer science. However, I do believe that delivering a high-performance GPU implementation is both technically challenging and a substantial contribution. Providing an efficient, ready-to-use implementation likely accounts for more than half of the paper’s value.

Moreover, as discussed earlier, the paper also contributes an algorithmic optimization unrelated to hierarchical attention itself but directly related to sparse attention implementation: the sparse-index-transpose based backward optimization can immediately improve existing VSA/SLA implementations. Overall, I do not think the algorithmic similarity materially undermines the paper’s contribution.

Future Directions

With current resources, my plan is to train a stronger DiT on ImageNet using LLSA. There has been recent work in this direction, such as PixelDiT. I want to see whether we can use LLSA to compute pixel-wise attention somewhere in the model without significantly increasing compute. For example, keep PixelDiT’s patchified encoder unchanged, and only increase attention cost in the decoder. But my recent experiments suggest this does not help much—removing patchification across the entire Transformer seems necessary. For now, I am still exploring low-cost variants.

If we switch validation strategy, another idea is 4K image generation: finetune a pretrained FLUX model on an ultra-high-resolution dataset. Prior work has done similar things but used window attention. Replacing it with LLSA should improve quality substantially. However, such application-driven work requires a much larger engineering effort, and shifts the focus from attention design to a specific task. It is better treated as a separate research project.

In my view, the most efficient path forward is collaboration—validating LLSA on more standard and suitable tasks such as NLP or video DiT generation. For NLP, I would need to connect with researchers working on attention optimization to seek feedback. For video generation, the main bottlenecks are data and compute, so we likely need to collaborate with an industry team. Since the paper studies attention mechanisms themselves, a serious follow-up should not be “small-scale finetuning of existing video models”; ideally, LLSA should be used throughout large-scale training.

Ignoring collaborators and compute constraints entirely, I believe the real stage for LLSA is tasks previously considered infeasible due to quadratic attention, such as voxel-based 3D generation. This year, there is already 3D generation work using sparse attention—for example, Direct3D-S2 adapts NSA to 3D generation and can handle up to 45K 3D latents. If GPU performance continues to improve linearly, and if a task’s quality depends directly on token count, then LLSA should have significant room to shine, because it truly reduces attention complexity.

Summary

In this work, we introduce Log-linear Sparse Attention (LLSA), a novel attention mechanism that reduces self-attention complexity from $O(N^2)$ to $O(N \log N)$. Its main contributions are:

A hierarchical design that reduces sparse attention complexity, which can be applied to essentially all types of sparse attention mechanisms.

KV Enrichment, a sparse-attention strategy that better preserves global context than VSA/SLA by attending jointly to sparse fine K/V and coarser K/V tokens.

A high-performance GPU implementation that we open-source. It can be directly adopted by future work, and its GPU programming insights may also inspire follow-up research.

I see significant potential for LLSA in future large-scale generative models. If I were leading video DiT training, I would immediately replace full attention with LLSA.

My experience in MLSys is still limited, and the paper and research methodology may have room for improvement. We welcome collaboration in various forms, including but not limited to:

- Critiques and suggestions on the paper.

- Academic collaborations with university labs.

- Industry internships or project collaborations.

I will continue to promote and explain the paper. Planned follow-ups include an “exclusive interpretation” blog post beyond the paper content (this post is essentially a restatement of the paper).

References

Attention

(FlashAttention) FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness

(MoBA) MoBA: Mixture of Block Attention for Long-Context LLMs

(NSA) Native Sparse Attention: Hardware-Aligned and Natively Trainable Sparse Attention

(SpargeAttention) SpargeAttention: Accurate and Training-free Sparse Attention Accelerating Any Model Inference

(Sparse VideoGen) Sparse VideoGen: Accelerating Video Diffusion Transformers with Spatial-Temporal Sparsity

(VMoBA) VMoBA: Mixture-of-Block Attention for Video Diffusion Models

(VSA) VSA: Faster Video Diffusion with Trainable Sparse Attention

(SLA) SLA: Beyond Sparsity in Diffusion Transformers via Fine-Tunable Sparse-Linear Attention

(MRA) Multi Resolution Analysis (MRA) for Approximate Self-Attention

(Radial Attention) Radial Attention: $O(n\log n)$ Sparse Attention with Energy Decay for Long Video Generation

Log-Linear Attention

Pixel DiT

(PixelFlow) PixelFlow: Pixel-Space Generative Models with Flow

(PixNerd) PixNerd: Pixel Neural Field Diffusion

(JiT) Back to Basics: Let Denoising Generative Models Denoise

(DiP) DiP: Taming Diffusion Models in Pixel Space

(DeCo) DeCo: Frequency-Decoupled Pixel Diffusion for End-to-End Image Generation

(PixelDiT) PixelDiT: Pixel Diffusion Transformers for Image Generation